Pop-up Cards: Montgomery, Alabama

Continuing from the previous issue, I made a pop-up card for the state of Alabama.

This time, I chose buildings in Montgomery, the capital of Alabama.

The first pop-up card model is the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

The church was founded in 1877 as the second black Baptist church in Montgomery, and the current building was completed in 1889.

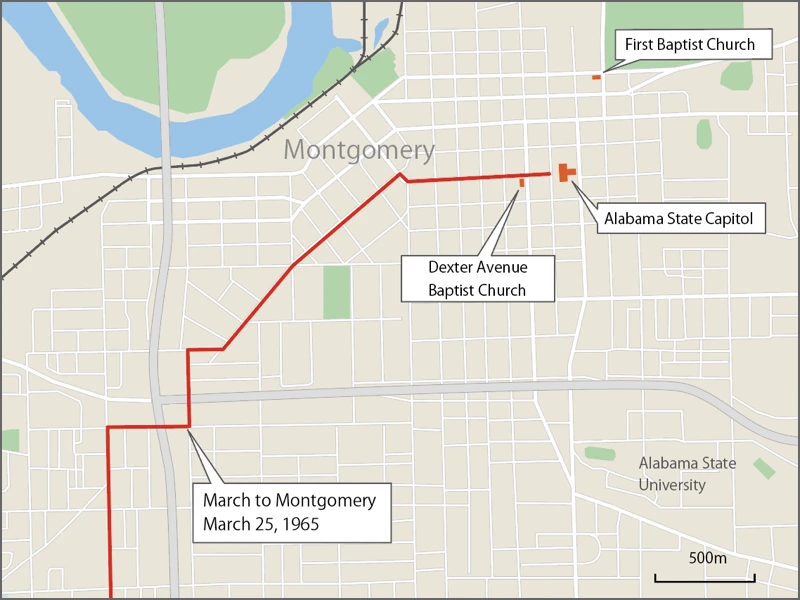

The church is where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. became pastor in 1954 after completing his graduate studies. It is located near the State Capitol (see map at end).

Dr. King led the bus boycott movement (1955-56) centered on this church.

The church is now called Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church.

The model for the second card is the First Baptist Church.

This church was founded in 1866 after the American Civil War, but there had been (and still is) a church called First Baptist Church before that. During slavery, blacks attended that church, but they were only allowed in the balcony.

In 1866, the Emancipation Proclamation was approved in Montgomery, and 700 black citizens established this church as an independent entity from the existing First Baptist Church. This was the first black Baptist church established in Montgomery.

The building built in 1867 was later destroyed by fire, so the present church was rebuilt between 1910 and 1915.

It was also nicknamed “Brick-a-day Church” because the congregation was asked to bring bricks at that time.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the church became a center for the civil rights movement. The following incidents occurred in this context.

In 1961, the “Freedom Riders” movement began within the civil rights movement.

At that time, city buses were governed by city and state laws, but interstate buses, which operated between states, were governed by federal law. In the north, blacks and whites were seated freely on interstate buses, but in the south, seating was segregated.

To confirm and protest this condition, activists (both blacks and whites) took action by moving freely in their seats and using the benches and restrooms at rest stops without following racial distinctions.

But this activity was met with an assault by whites.

After being assaulted at a bus stop in Montgomery, the Freedom Riders sought refuge at First Baptist Church. Dr. King addressed a rally to encourage them, but 3,000 whites surrounded the church and they were locked in for 15 hours until the FBI and Alabama National Guard were dispatched.

The third card is the Alabama State Capitol.

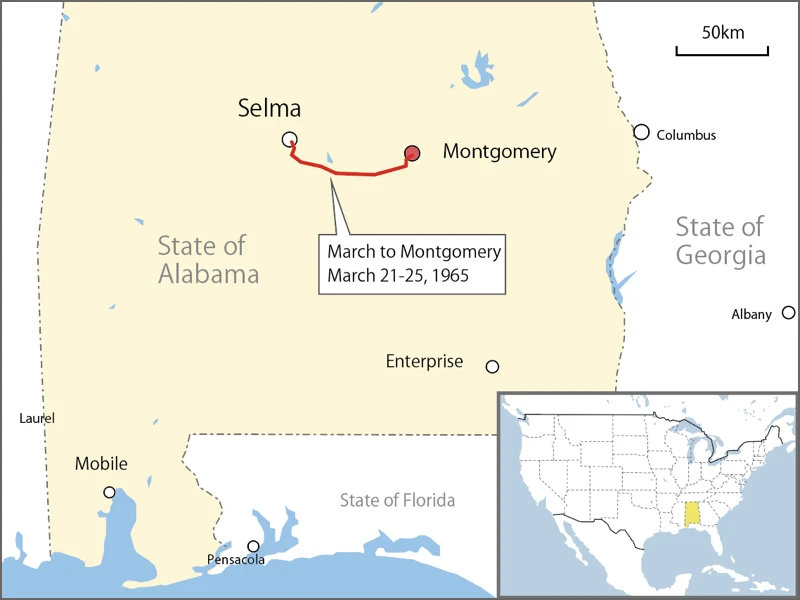

In my last article, I wrote about the march from Selma to Montgomery in March 1965.

The March 7 protest march for voting rights was suppressed by the police and dubbed the “Bloody Sunday” incident.

Two days later the march was stopped and shortened by the courts, but a third march was held.

The marchers left Selma on March 21 and walked more than 80 km to Montgomery. Along the way, the number of people was limited on roads with few lanes, but on March 24, people who had arrived by bus or car joined the march, and by evening there were several thousand people.

By the time they reached the Alabama Capitol on March 25, 25,000 people had gathered.

Dr. King delivered a speech known for the phrase “How Long, Not Long” here.

“I know you are asking today, 'How long will it take?’

Somebody’s asking, 'How long will prejudice blind the visions of men, darken their understanding, and drive bright-eyed wisdom from her sacred throne?’

Somebody’s asking, “When will wounded justice, lying prostrate on the streets of Selma and Birmingham and communities all over the South, be lifted from this dust of shame to reign supreme among the children of men?"

(omitted)

I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, because 'truth crushed to earth will rise again.’

How long? Not long, because 'no lie can live forever.’

How long? Not long, because 'you shall reap what you sow.’

How long? Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice."

The Voting Rights Act subsequently passed Congress and was signed into law by President Johnson on August 6.

[Reference]

“The History of African Americans in America" (James M. Vardaman, translated by Yutaka Morimoto, / NHK Publishing / 2011) (written in Japanese)

“The History of African Americans in America, Expanded Edition" (Shinobu Uesugi / Chuko Shinsho / 2024) (written in Japanese)

“How long, Not long" (wikipedia /2025ー01ー28 reading)

Discussion

New Comments

No comments yet. Be the first one!